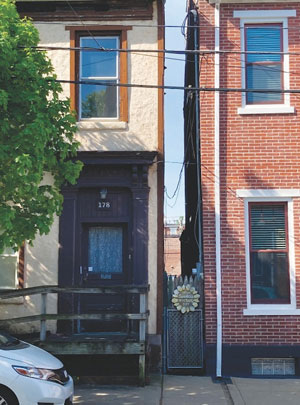

The first is a simple space between two sets of row houses. The second type is a corridor or tunnel between two connected row houses and of these there are two flavors—the street level tunnel and the underground tunnel (down a few steps, through the houses, and back up to the backyard). The straight-through passageway will take valuable living space from one (or both) of the houses, while the underground passageway will take space from the basement(s).

Many are gated—some practical, some ornate, and some whimsical. While these passageways allow access to the backyards, more often than not they are now storage areas for trash and recycle cans, bikes, ladders, building materials, and more.

Bisecting these main streets are the alleys (or “ways” in Pittsburgh’s vernacular). If the spacing between the main streets is narrow, the garages, parking pads, or backyards of the row houses on the main street abut the alley. If the spacing is wide, then another set of row houses will front the alley.

What may not be readily obvious is that the breezeways from these row houses do not, in many cases, connect to just their backyards but to a walkway that extends through the backs of all the rear-facing row houses. If you look carefully, some of these pathways will exit out to a street or alleyway.

Many deeds, though, do not explicitly spell this out. Some reference long-forgotten surveys, and some have been lost over time as lots. These backyard easements are slowly disappearing, as they become overgrown, are fenced off, and adjacent homeowners mistakenly expropriate the property for their grills and sheds.

The historical question is, Why do these breezeways and rights-of-ways exist? Not much written can be uncovered, but asking longtime residents have revealed a number of conjectures.

Another reason dates back to when Lawrenceville was a working-class neighborhood. When the millworker, rail worker, or factory worker would come home, the passageways allowed them to come in through the kitchen rather than soil the living room.

In these turn-of-the-(last)-century row houses, the kitchens would have had coal stoves and iceboxes. The deliveries of ice and coal could happen via the passageways, again keeping them from coming through the living room.

I’m not sure if any—or maybe all—of the reasons are valid. Next time you are out and about, look at these fascinating breezeways and see if you can find the easements that exit out onto the streets.

David Conover is a local historian and writer who regularly contributes to the Lawrenceville Historical Society periodical Historical Happenings.